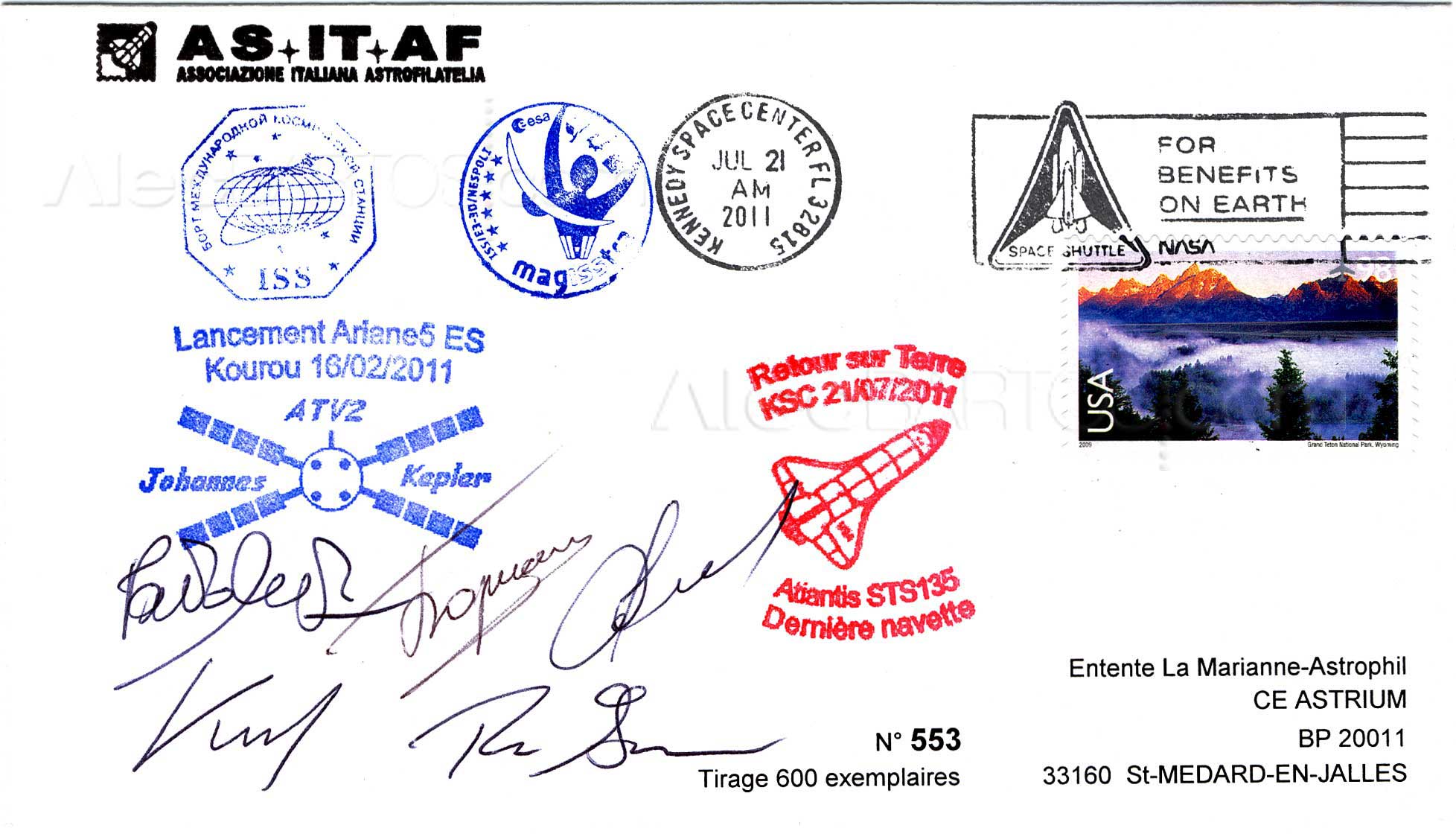

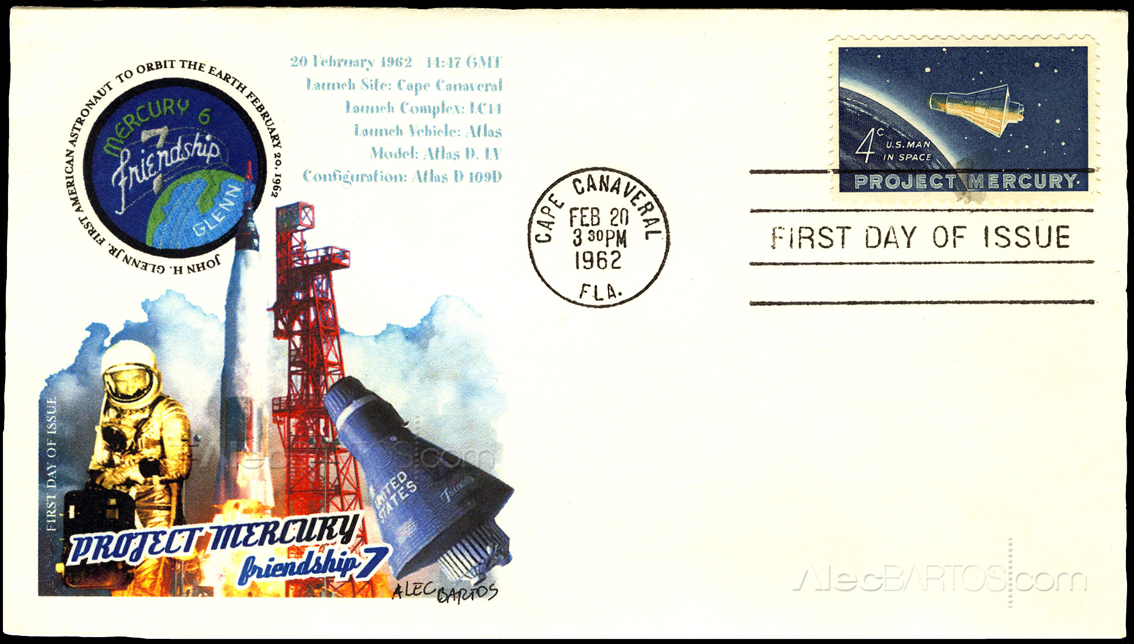

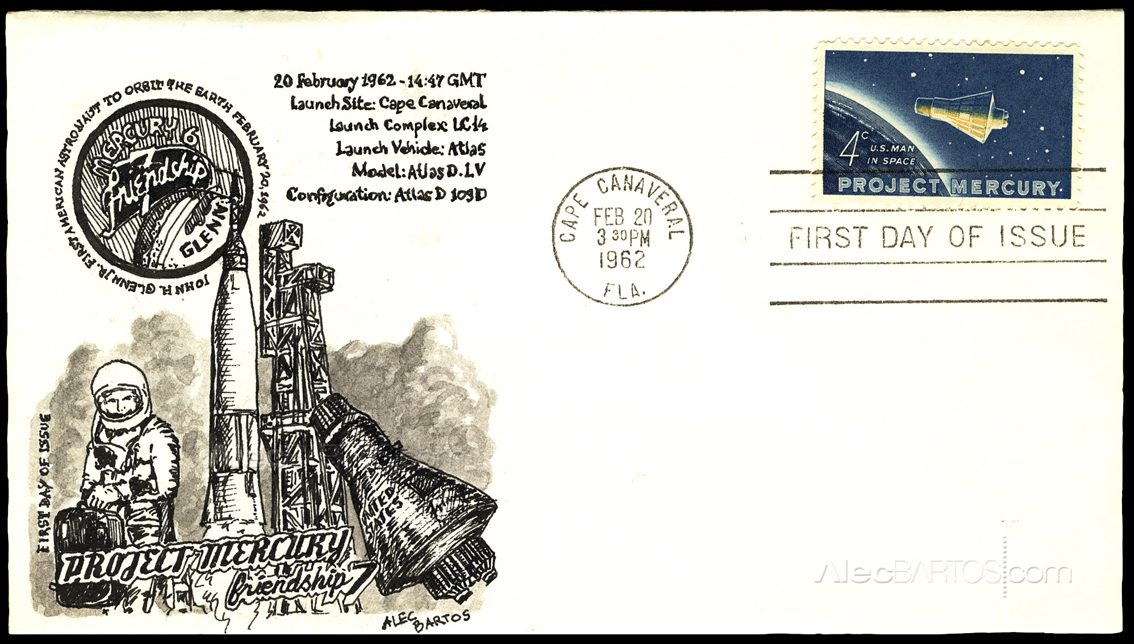

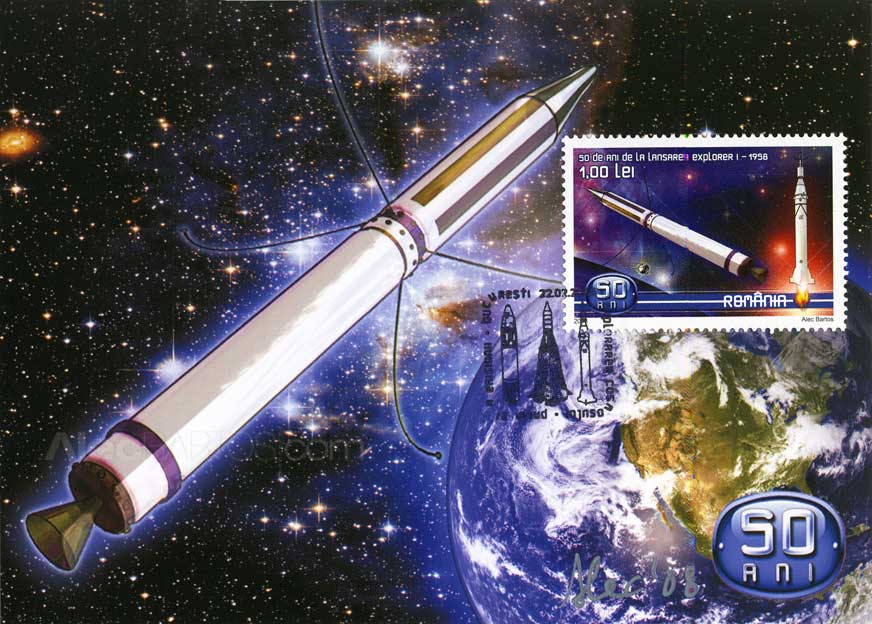

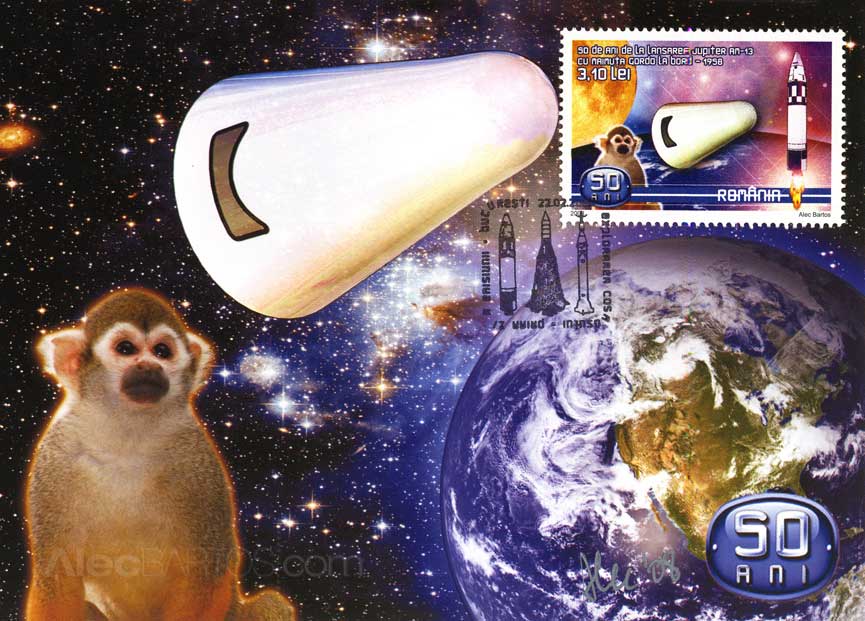

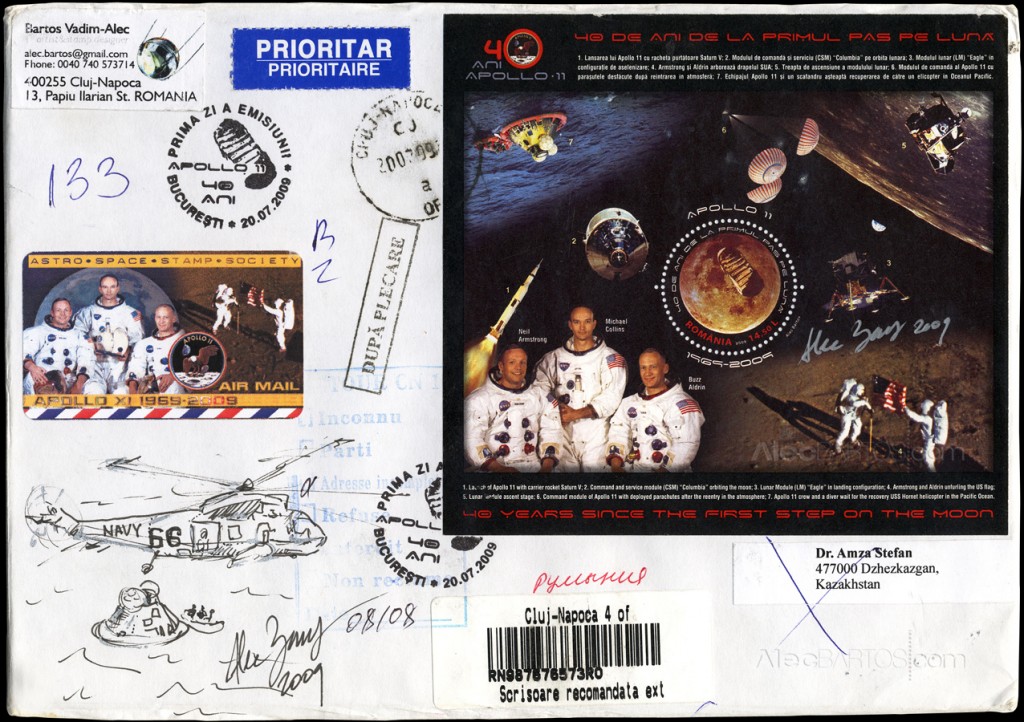

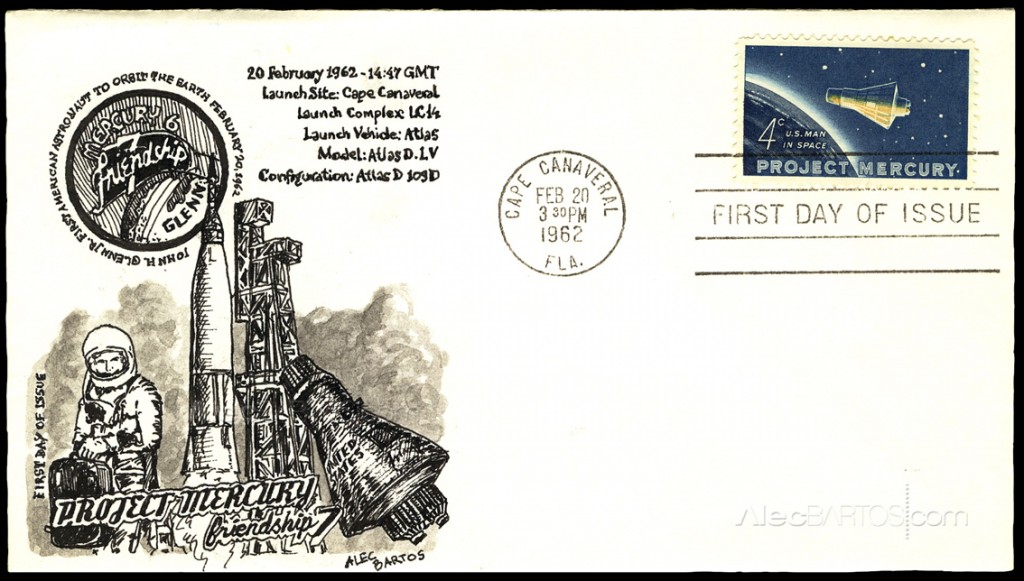

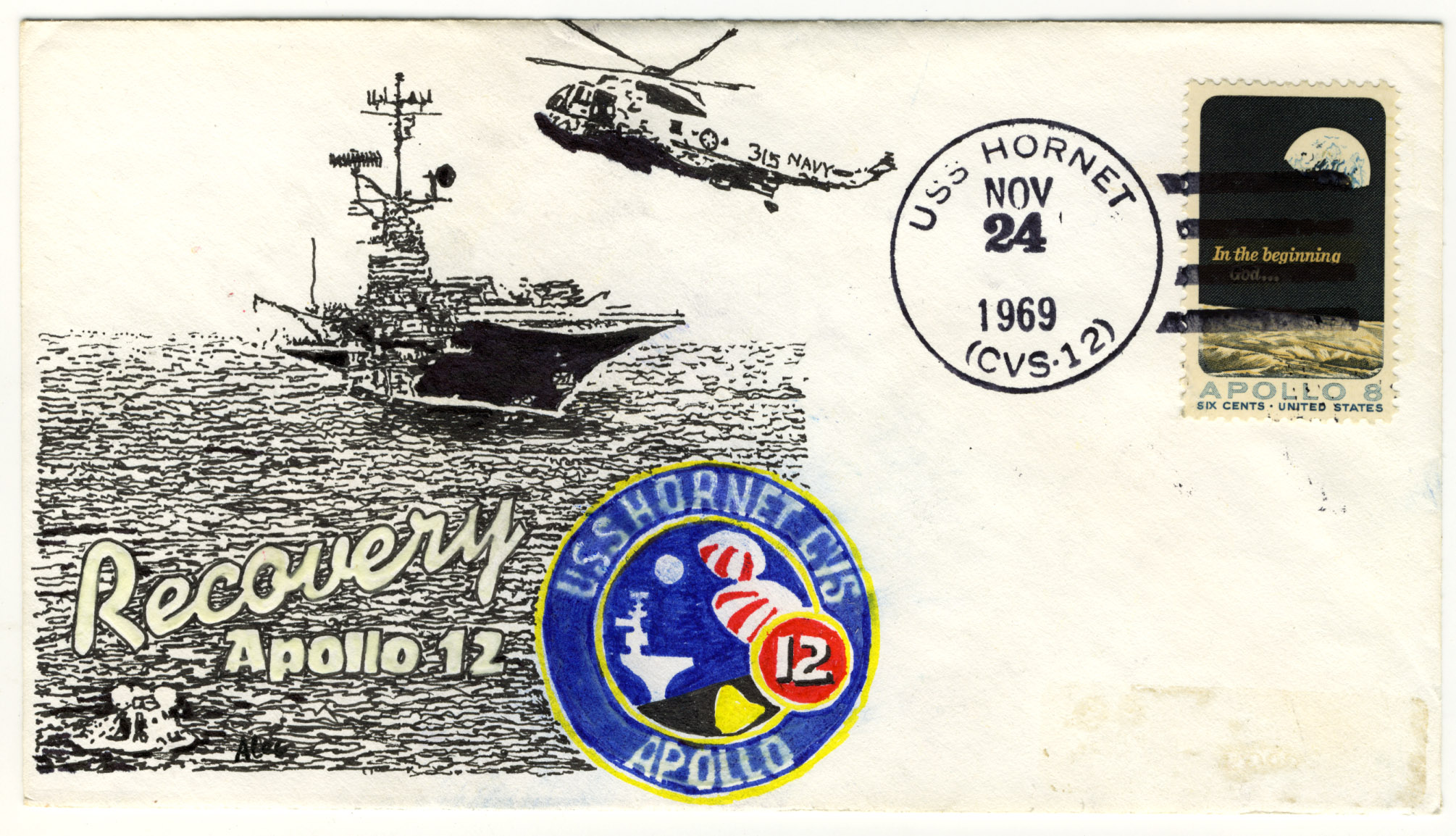

space cover cachets – handpainted

- September 12th, 2011

- Write comment

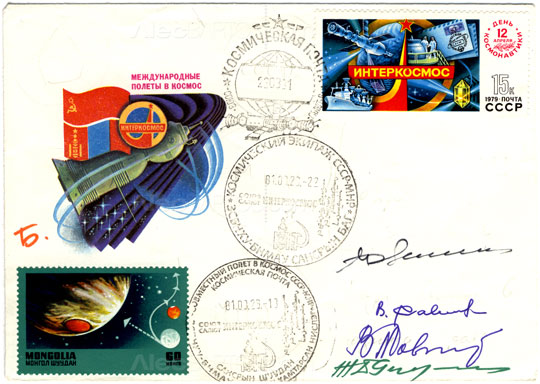

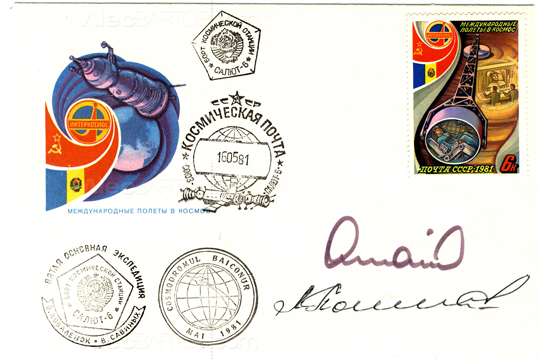

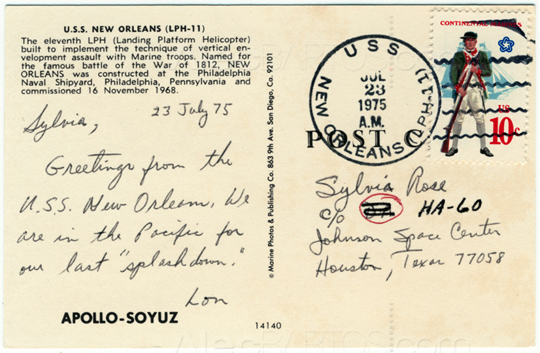

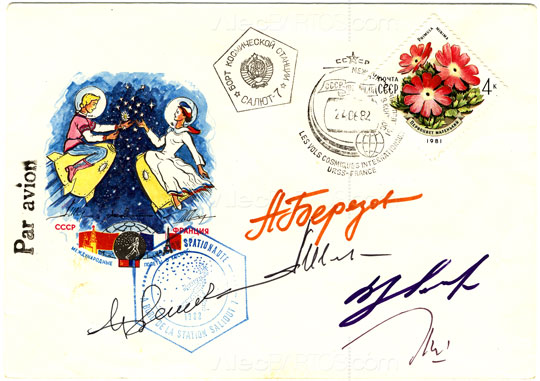

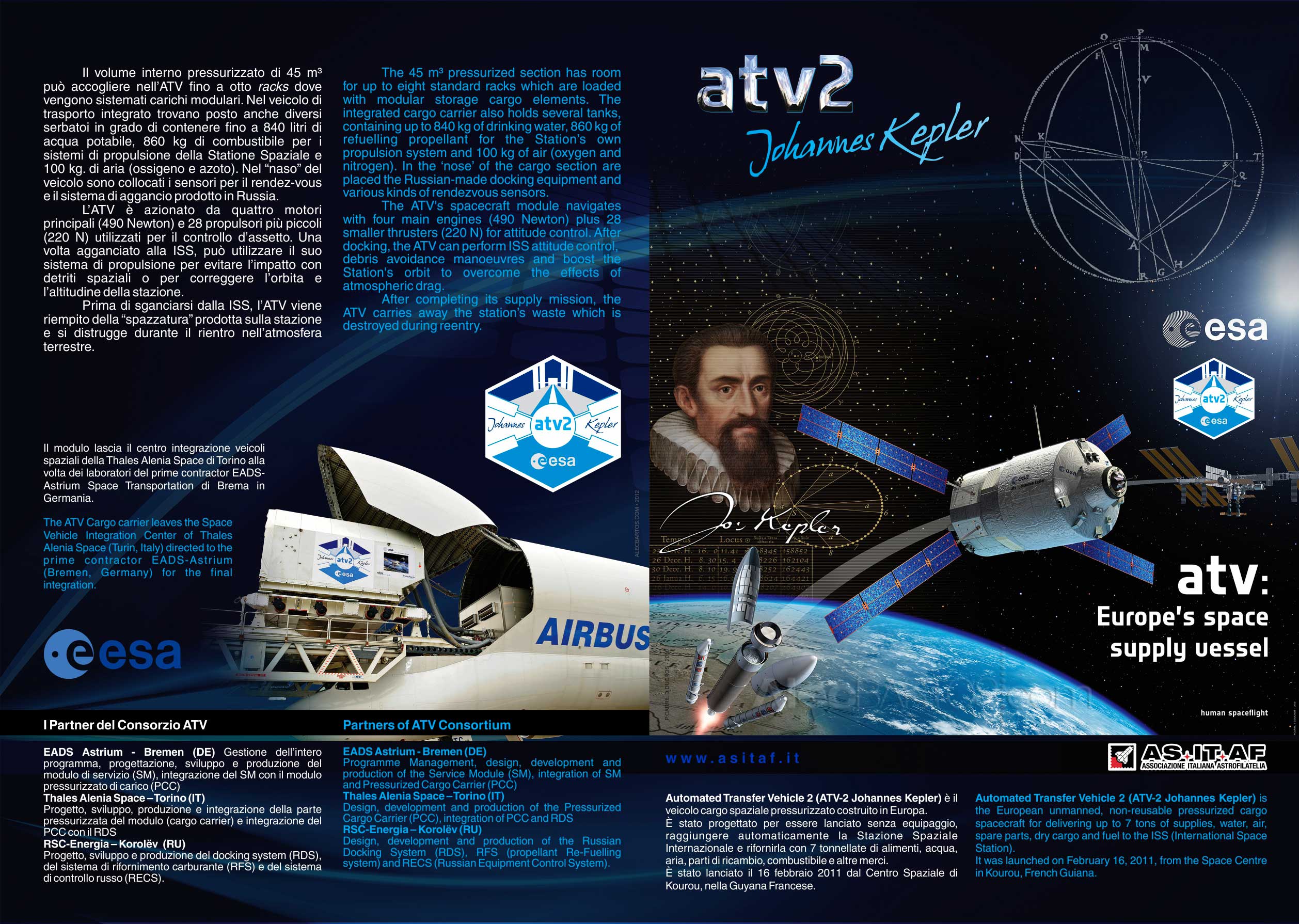

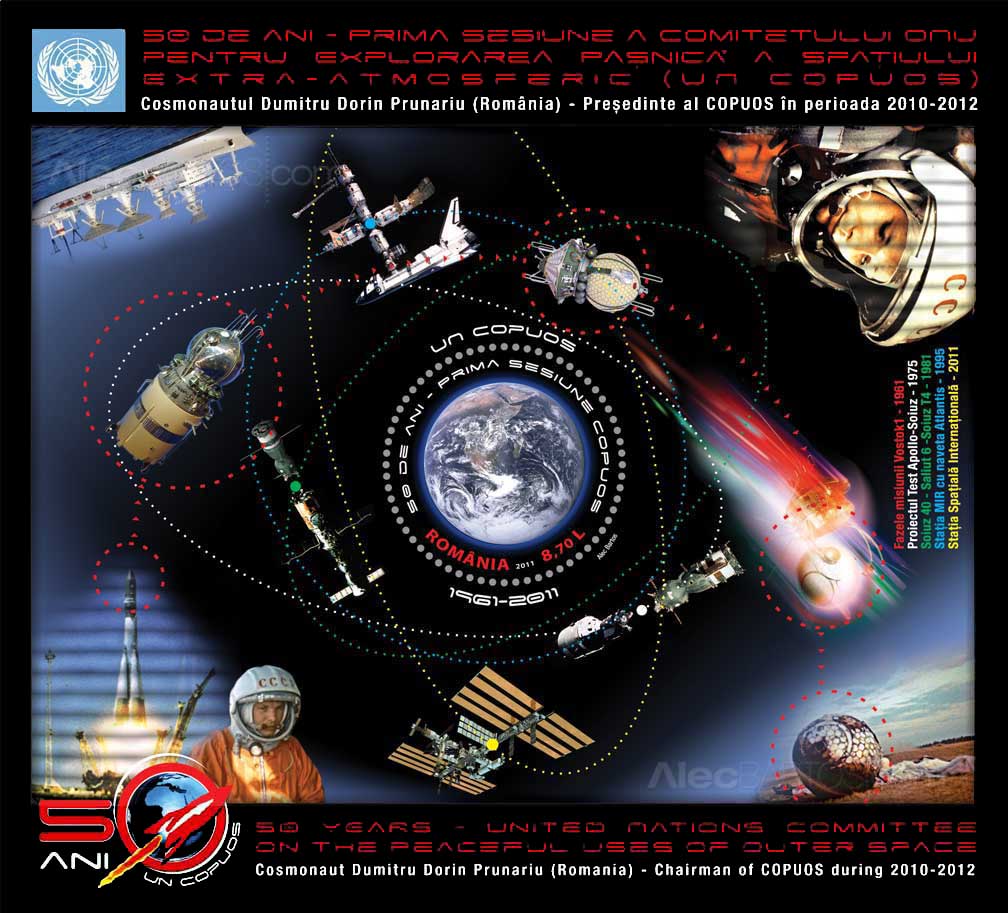

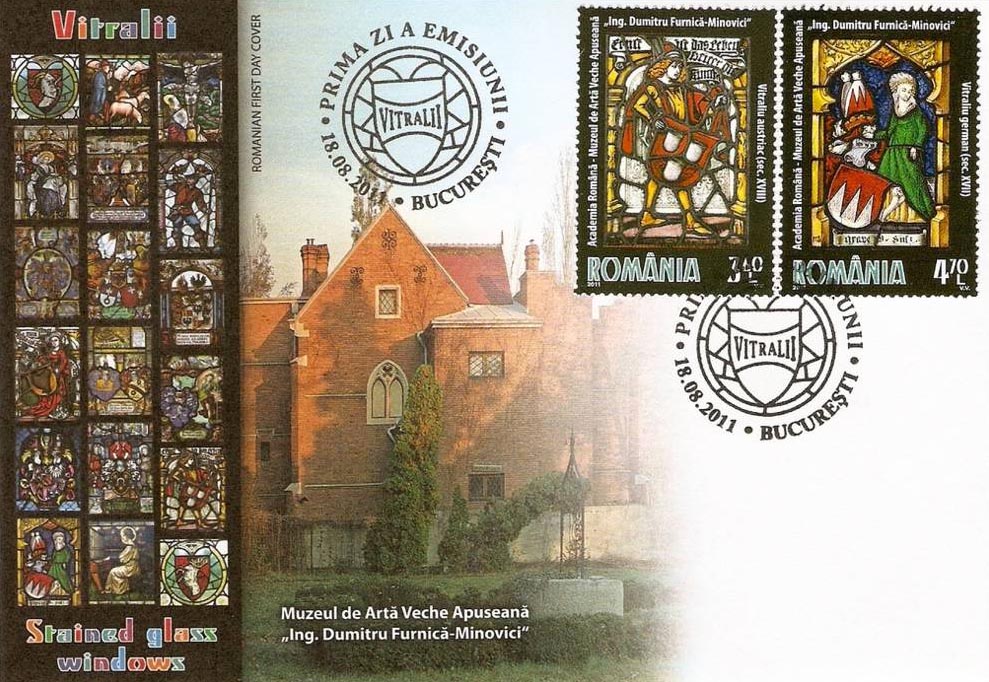

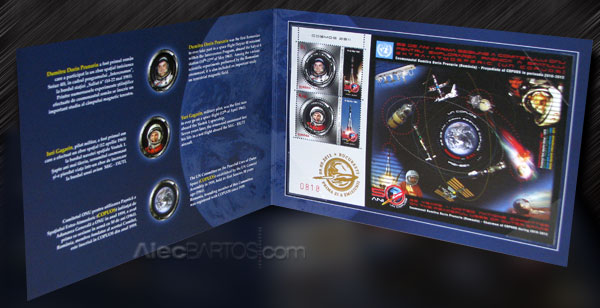

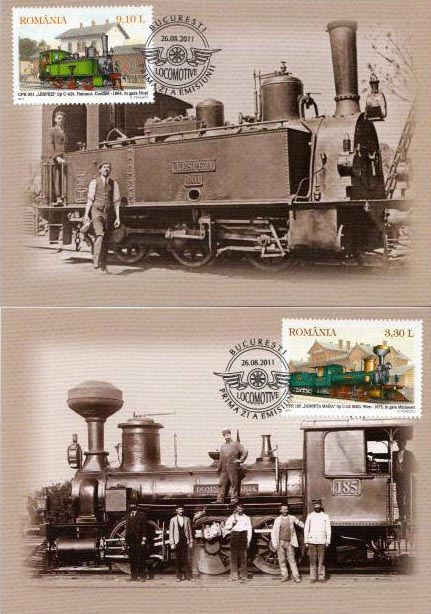

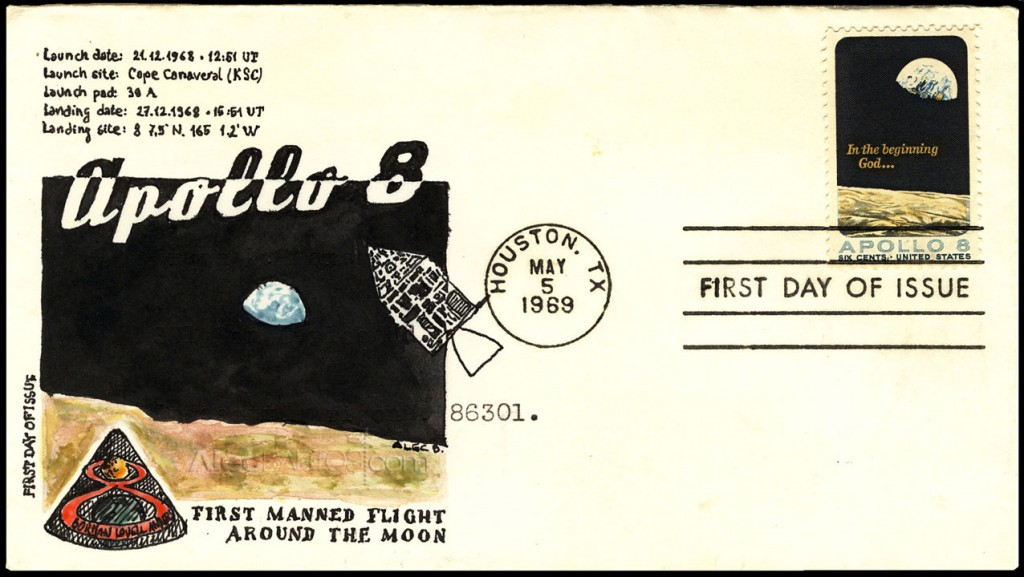

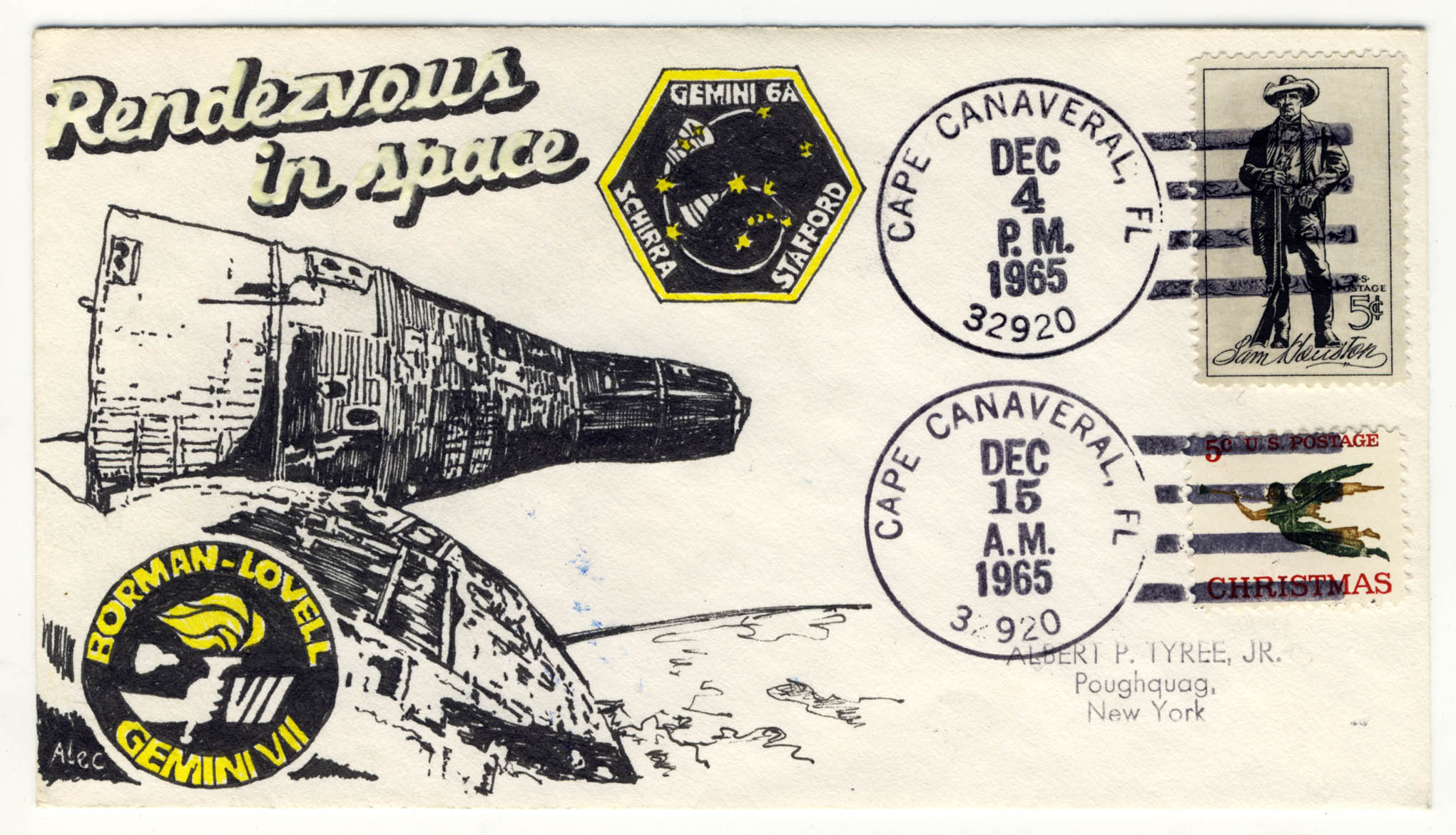

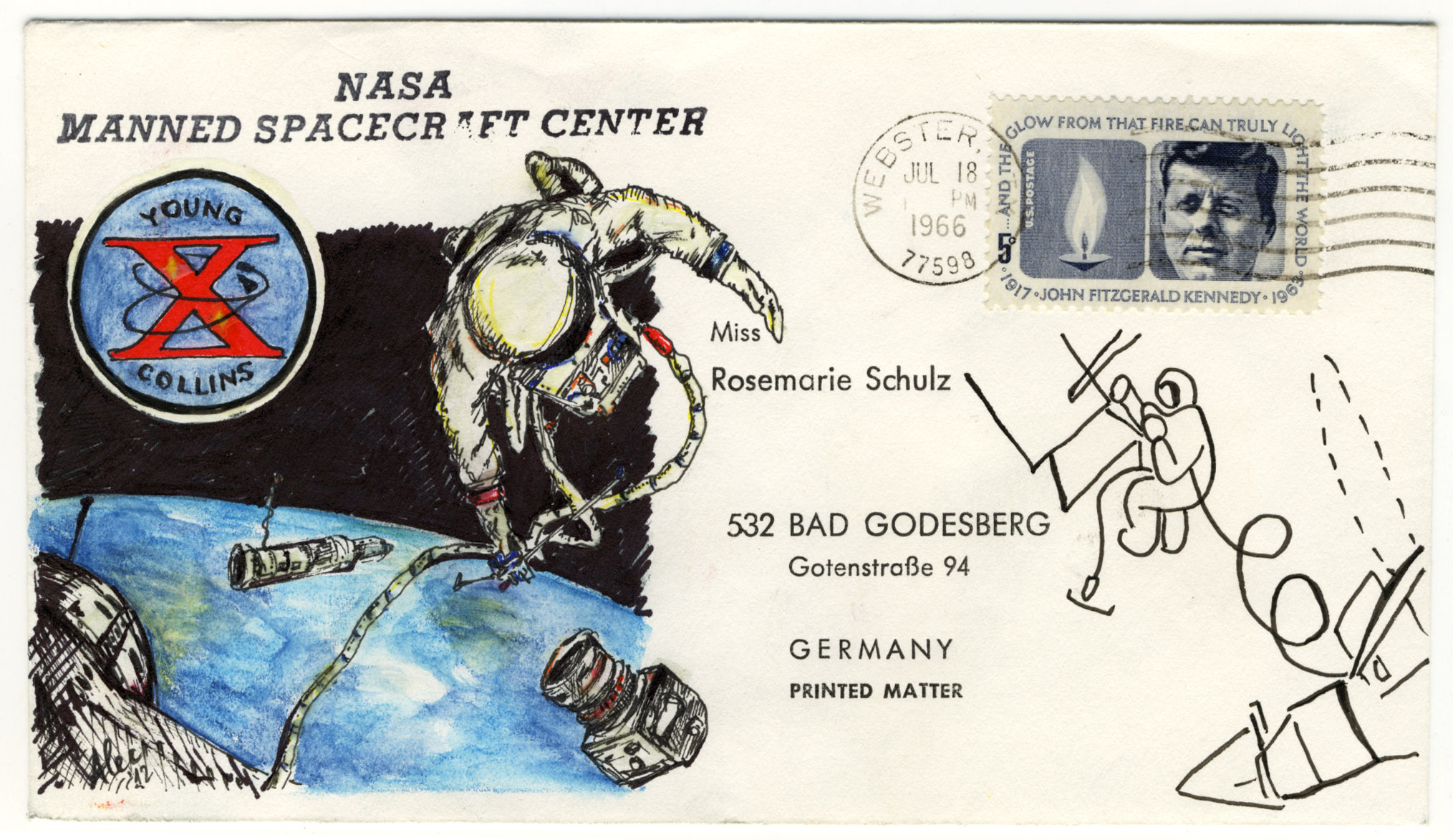

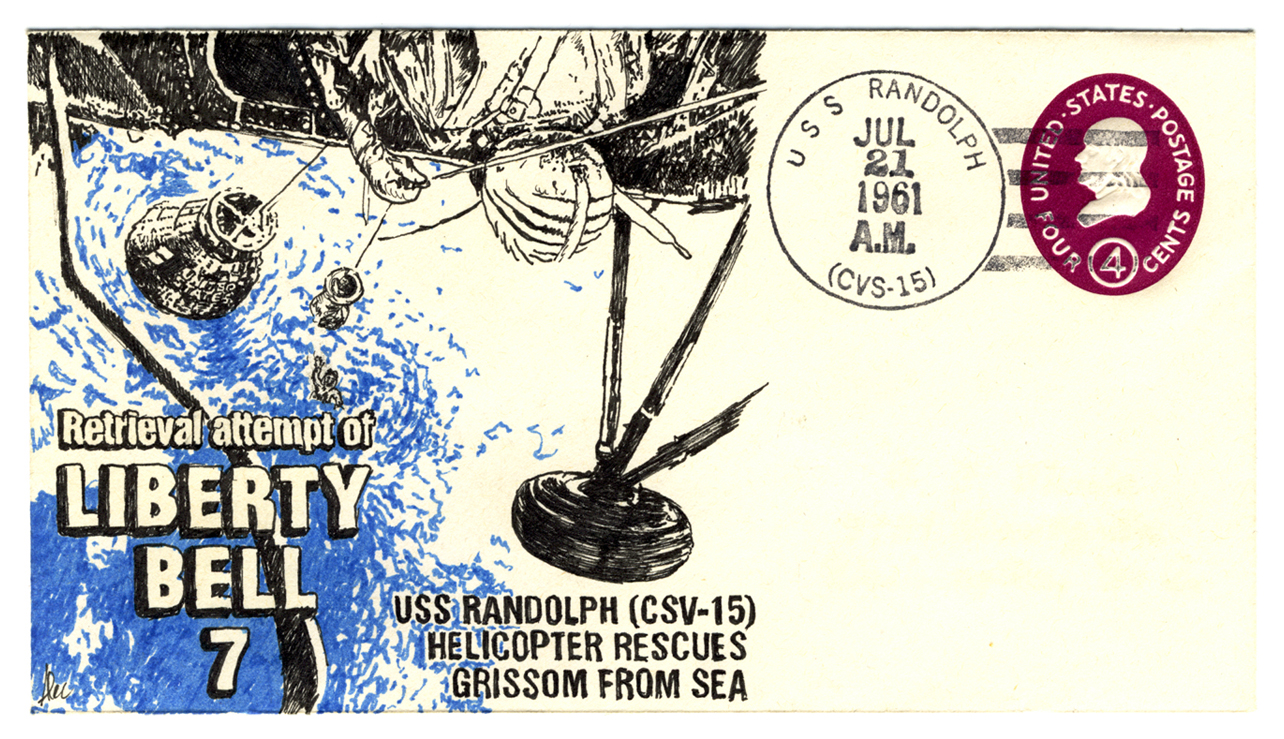

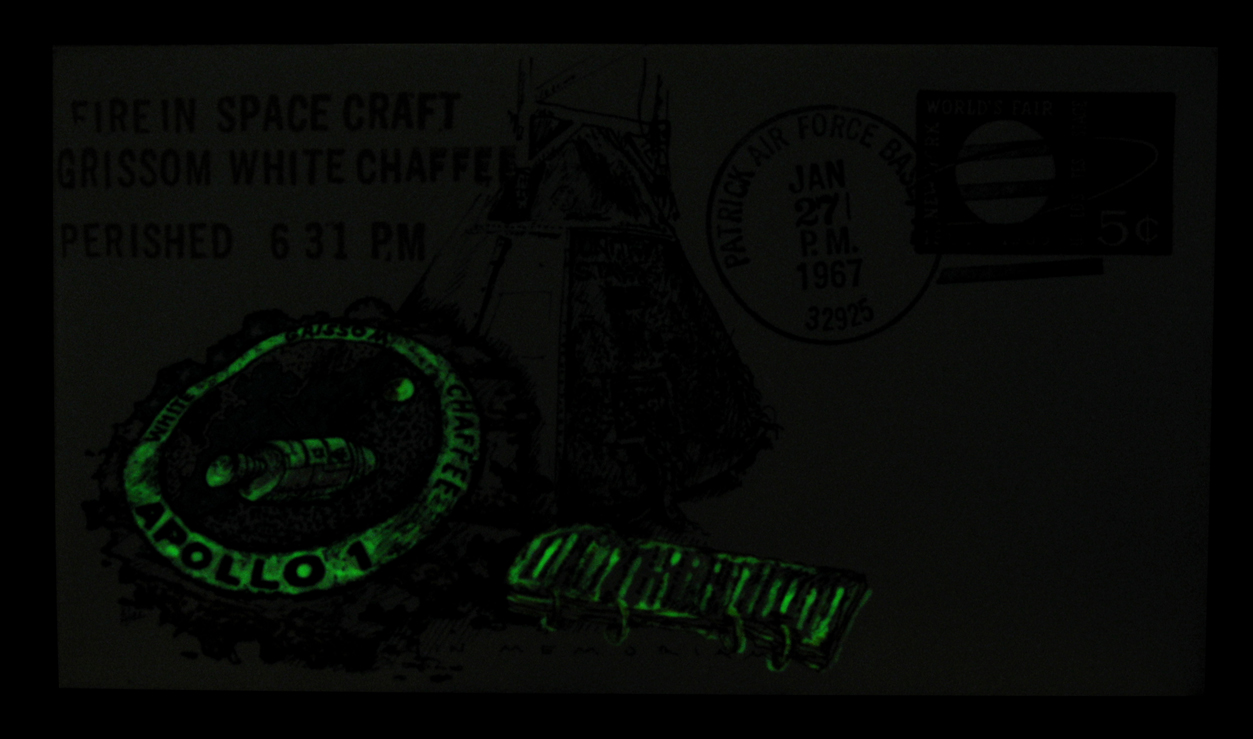

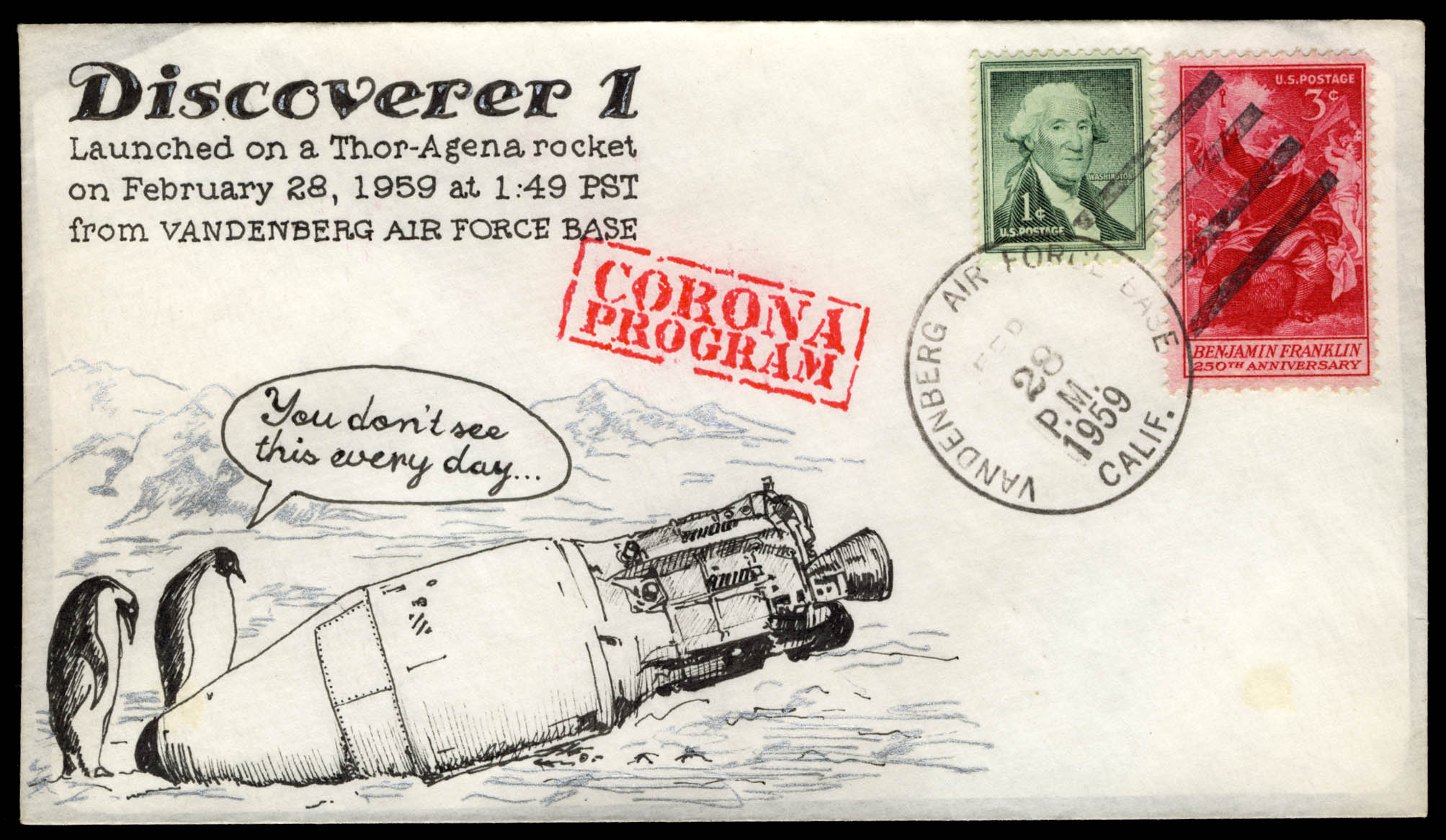

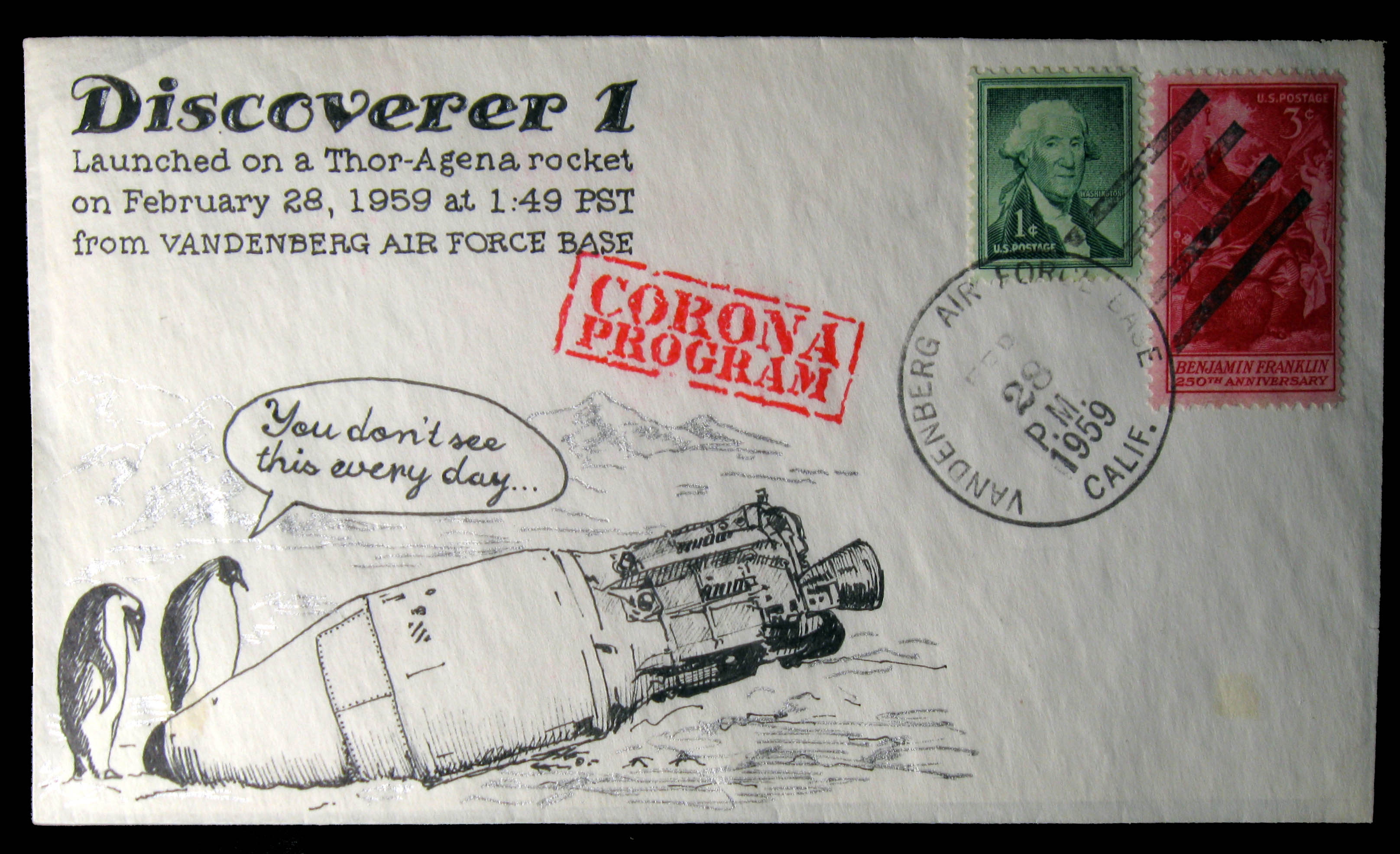

Cachet: In French, cachet means a stamp or a seal. On a cover, the cachet is an added design or text, often corresponding to the design of the postage stamp, the mailed journey of the cover, or some type of special event. Cachets appear on modern first-day covers, first-flight covers and special-event covers.

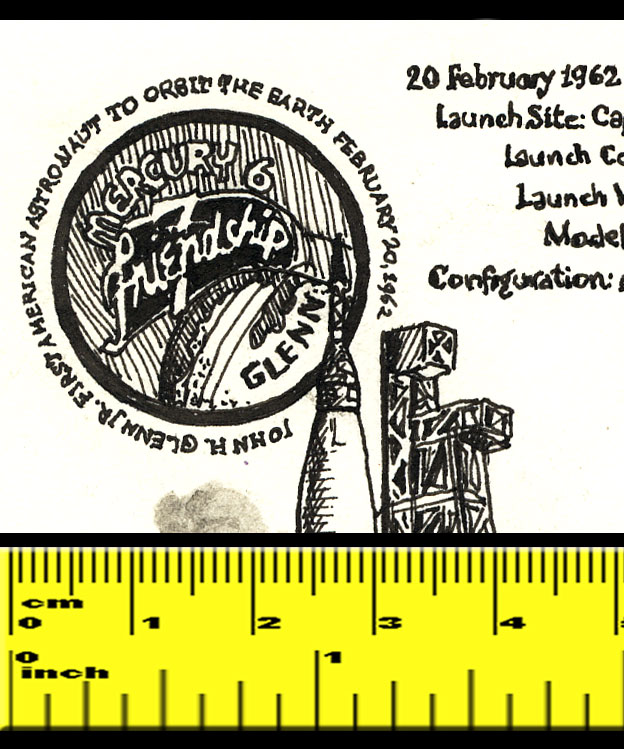

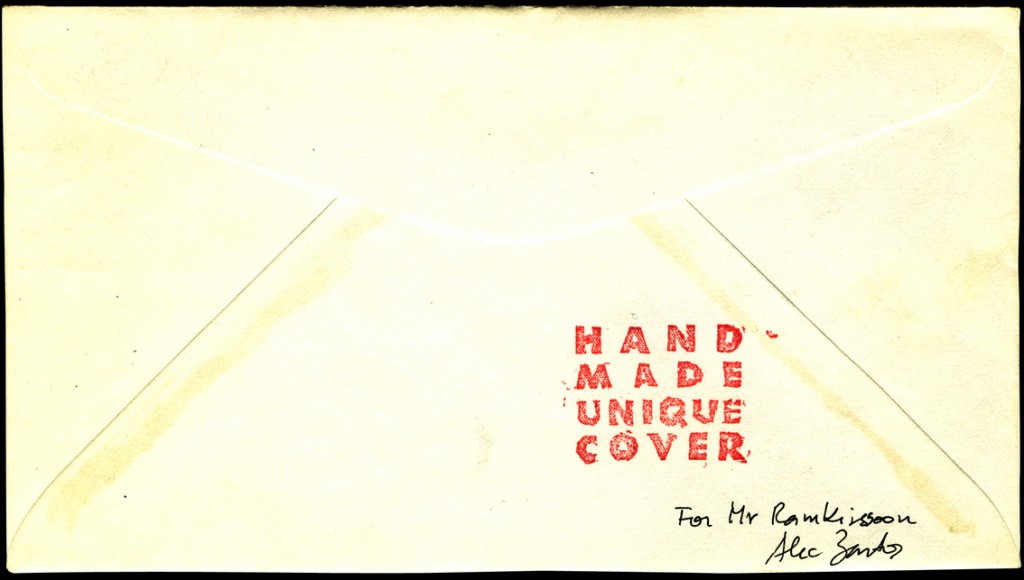

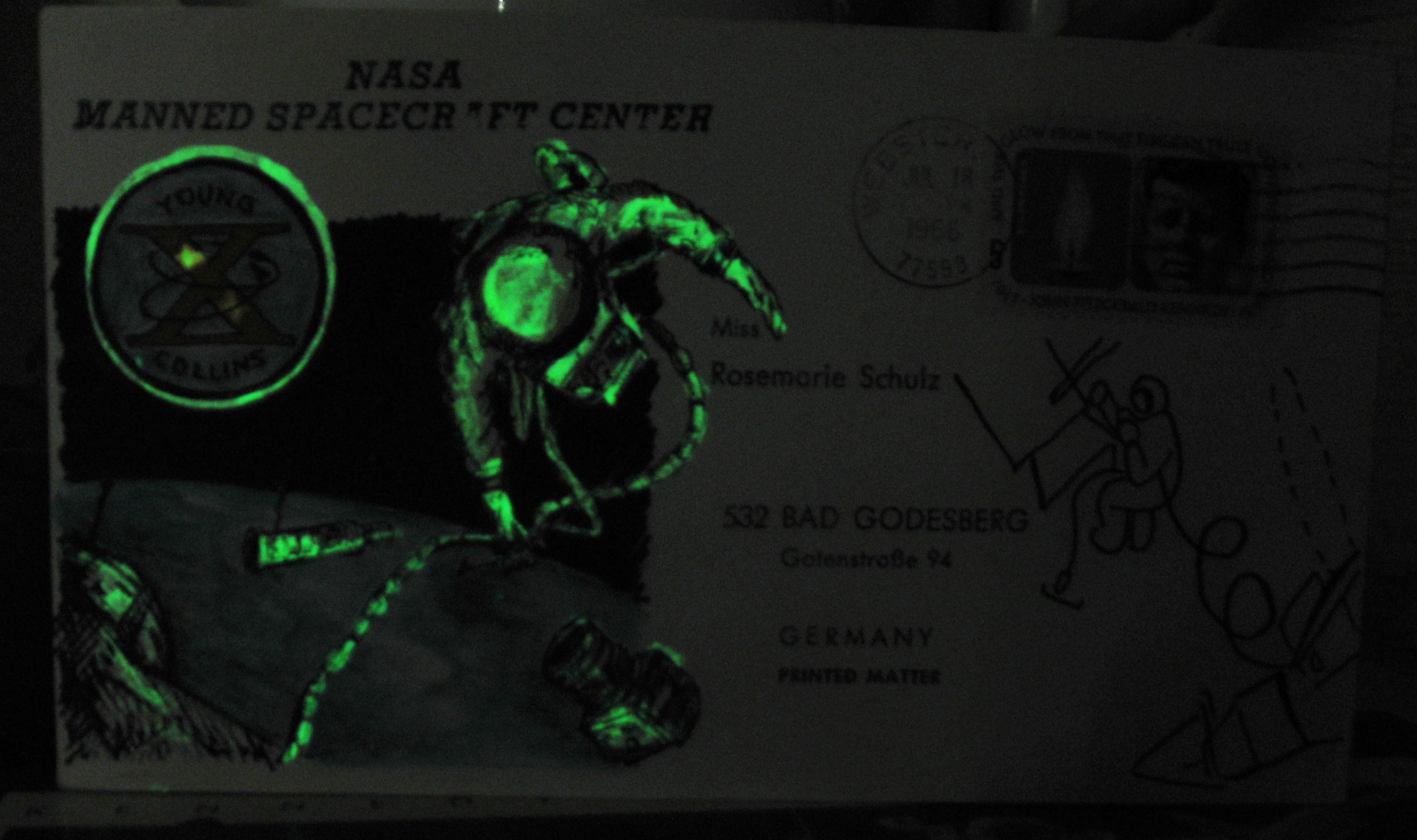

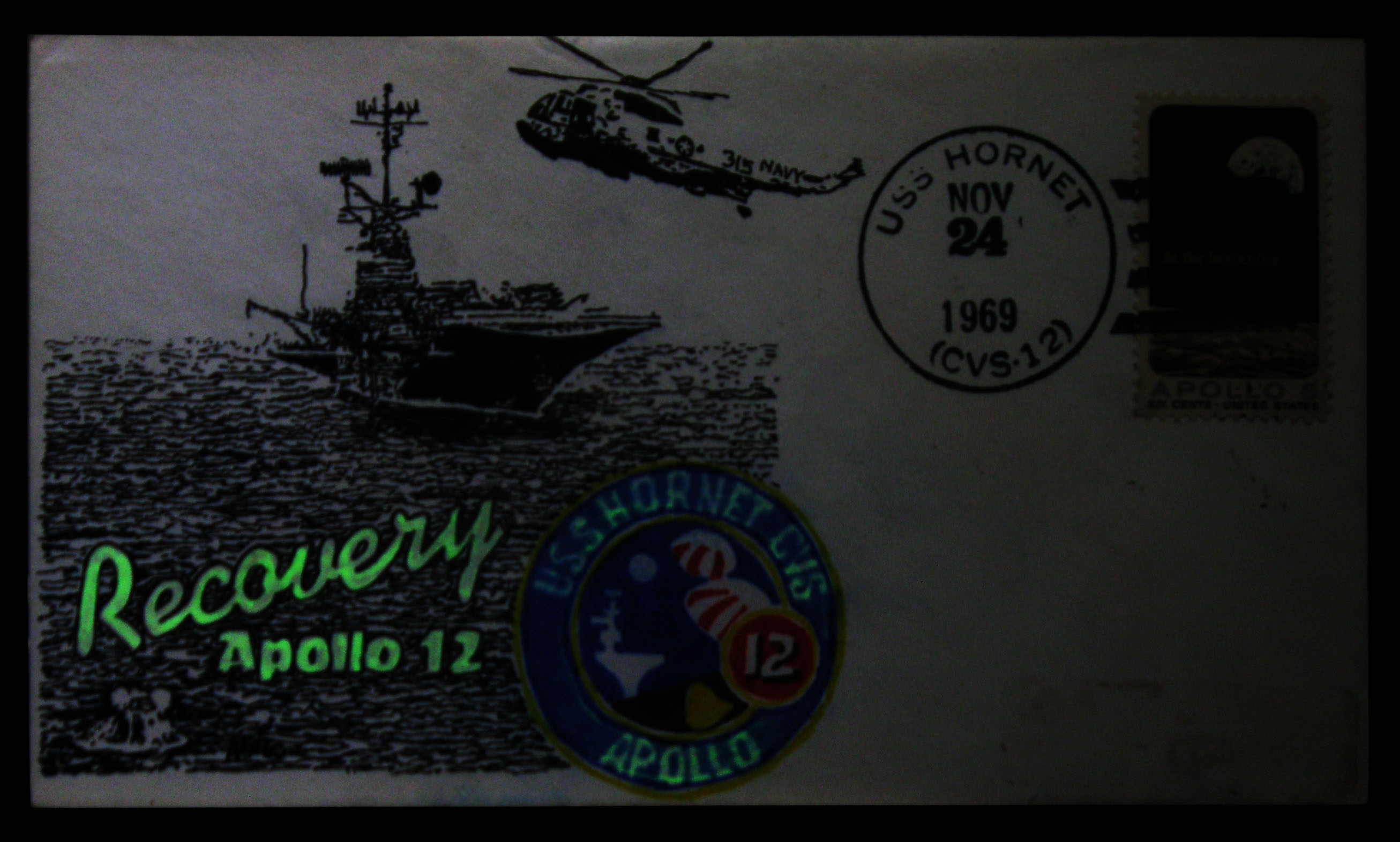

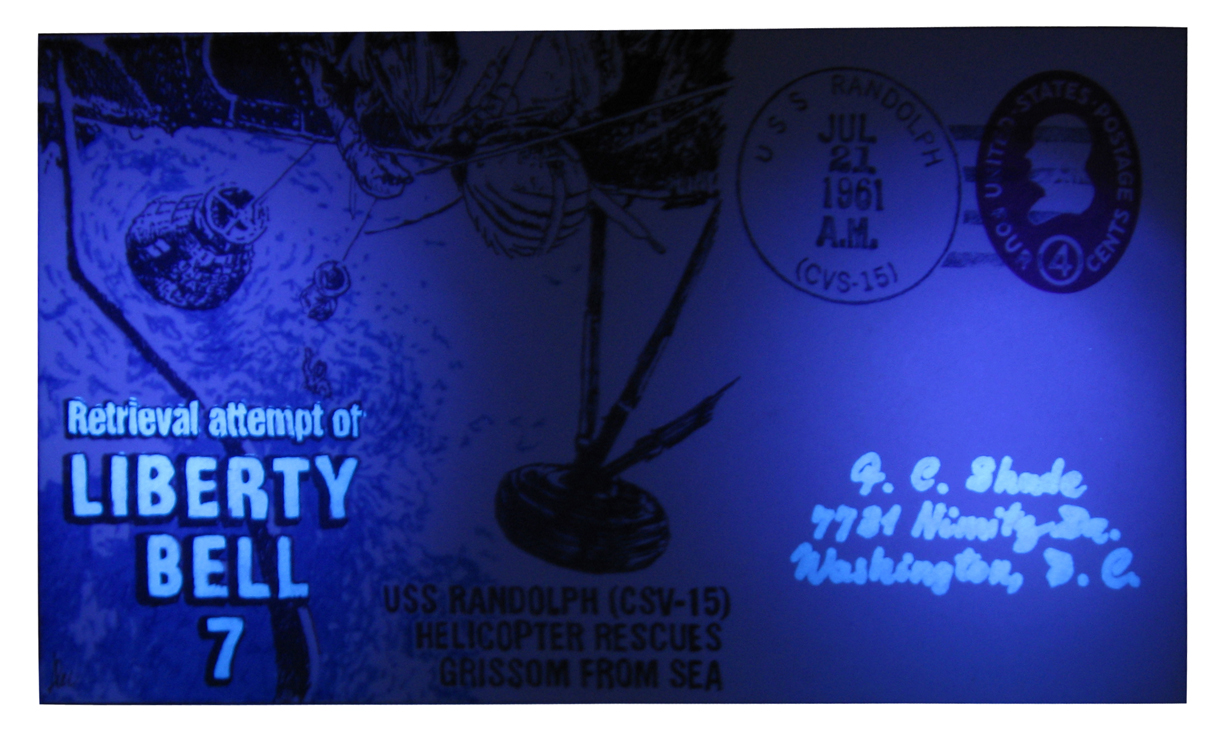

All the cachets are totally hand made, worked under the magnifying glass with nibs and brushes. Pigments used are inks and gouaches. In the darkness some features are photoluminiscent (glow in the dark pigments). The postmarks and stamps are originals from the respective period and places. Actual covers size are approx. 16,5X9 cm (6,49X3,54 inch) For details please click the images.

All the cachets are totally hand made, worked under the magnifying glass with nibs and brushes. Pigments used are inks and gouaches. In the darkness some features are photoluminiscent (glow in the dark pigments). The postmarks and stamps are originals from the respective period and places. Actual covers size are approx. 16,5X9 cm (6,49X3,54 inch) For details please click the images.

The Liberty Bell 7 cover has some features made with UV sensitive pigment. The cover bears a fake USS Randolph cancellation made by the famous forger Charles Riser. He was caught with the use of this kind of UV markings.

The Discoverer 1 – CORONA cover has silver paint effects. The cachet look different depending of the angle of the light (Éclairage).